| A Pace Odyssey |

|

- Home

- Mr. Pace

-

Dual Credit

-

English IV

- Honors English II

- Senior Project

- New Page

- Drama

-

Resources

- Readbox (Book Checkout)

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- MLA Format and Citations

- "Word Crimes" (Spelling and Grammar 101)

- Banned Books Week

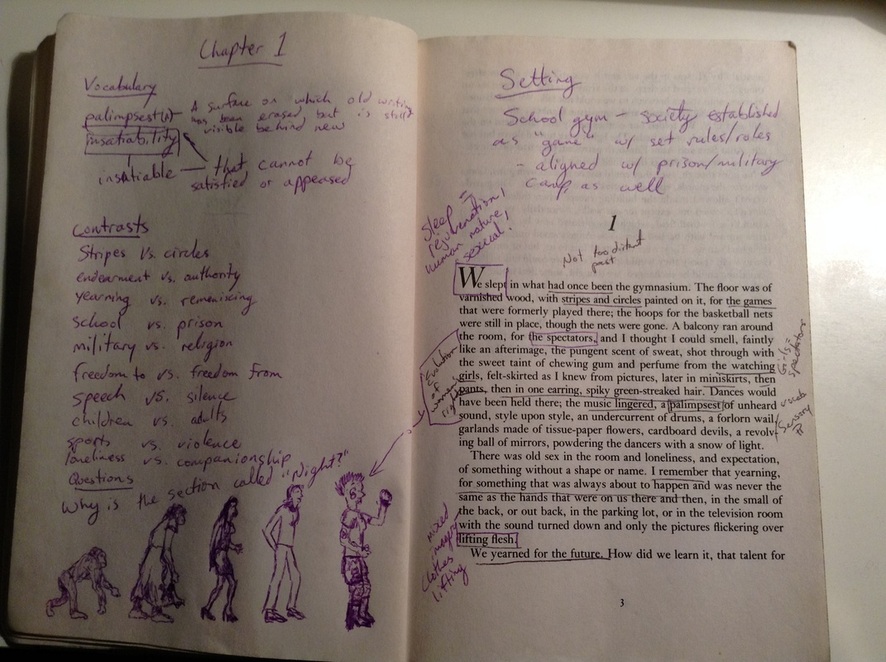

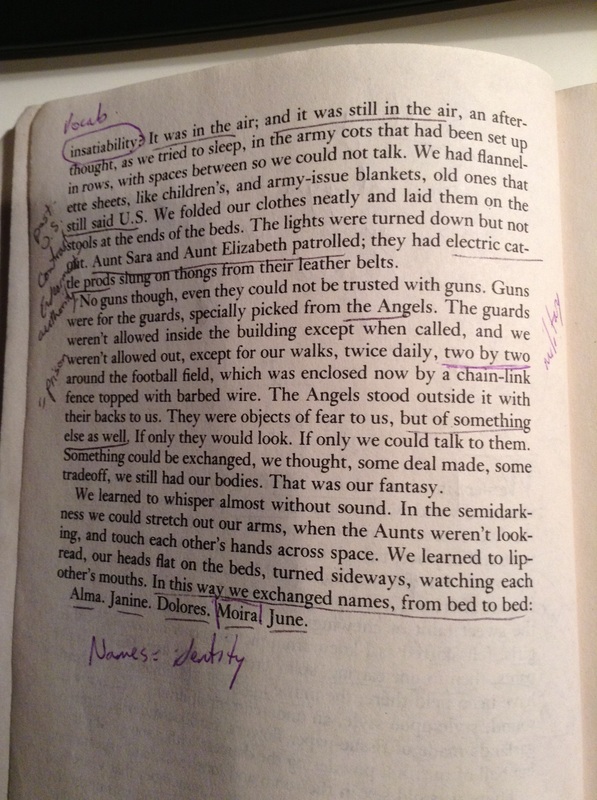

- How to Read Literature Like a Professor (A.P./Dual Credit Videos)

-

Previous Years' Pacebooks

>

- Dual Credit 2018-19

- Dual Credit 2019-20

- Dual Credit (2020-21)

- English IV 2018-19 (3rd Period)

- English IV 2019-20 (3rd Period)

- English IV 2020-21 (4th Period)

- Honors English II 2018-19

- Honors English II (2019-20)

- Honors English II 2020-21

- English IV 2021-22 (4th period)

- Pacebook (4th Period) 2022-23

- Honors English II 22-23